I dreamt of my father last night.

I was on a couch in the middle of a wonderful conversation with a dear and intimate friend, when I looked up and discovered that the wall before us had given way and opened onto a beautiful garden, lush with green leaves and pops of color, running water, tall trees – spaced out from one another – and brown pathways of soil. And the garden was people with ones both living and dead. Most were strangers to me, but I could see that the living had found their beloveds among the dead because they were beginning to pair off. Those still alive in this life looked just like me. But those who had died lacked color, as though they were actors in a black-and-white movie, their faces and hands various shades of gray. But their clothes were just as colorful and vibrant as all the rest.

So when I saw my father, though his face and hands were grayscale, the button-down shirt he wore was baby blue, the white note cards and black pen sticking out of the breast pocket, and his khaki pants almost blending in with the pathway beneath his feet, shod in brown shoes with their thick soles.

My heart leapt when I saw him as he stood, watching me, waiting for me to see him on just the other side of the would-be wall. I felt the tears prick in the bottom wells of my eyelids and I turned back to my friend, explained how much I was enjoying our time together but that I couldn’t lose this opportunity to be with my dad. And I ran to him.

Reliving the dream now, I am shocked that I didn’t run straight into his arms, the safest place I have ever known. But I didn’t. I just ran to him, close enough to feel the slight heat from his body, and clasping his right hand in my left, spent a moment looking up at him, at his straight white teeth beneath his moustache. And then we turned and began to walk, still holding hands, as we would have done when I was a very small child.

And as we walked, I poured out my heart to him, the tears streaming down my face, the sobs escaping from my beaming smile. I told him how much I missed him, how hard it is to live this life without the wisdom and strength of his presence. I told him about my book – I remember that distinctly – that it was all about my grandmother but that I wrote it, in the end, mostly for him and that I hoped, that I knew, he was proud of me. And I soaked up his gladness. And I woke happy.

Later, in the car on the way to church with my family, the radio playing its precisely random series of songs that no playlist could ever replicate – Sia and Green Day, Mary J. Blige followed by Pat Benetar – the dream came back to me.

And I realized it was not my only dream last night. Before that, before my father, there was another dream, unrelated. I watched first-hand as half a dozen men were skydiving, falling rapidly through the clouds. I observed them just after they had left the plane, which was still jetting off beyond their heads. For I was with them, right beside them, but I was just an observer, in the way of dreams, not also skydiving, too.

And while five of them were professionals, dressed in special suits and black-visored helmets so that I could not see their faces, I had the sense that the sixth man wasn’t meant to be there. As though he had been pushed off the plane, or perhaps was supposed to be strapped on to one of the others but had somehow come undone. This man, the mistaken skydiver, had light-brown skin and his shoulder-length hair, his beard and moustache, were all dark. He wore what looked like a light-weight hoodie, a few sizes too big for his thin body, for as he fell through the sky, it flapped about him every which way.

The poor man was panicked. Terror lined his face and shone from his eyes as he hurtled towards the earth. Watching alongside of him, I felt a pang of his panic, as though, for a moment, his feelings were mine. And then the anxiety I felt for him was my own, for as I saw the hoodie expanding and contracting and blowing about his body, I realized that there were no straps around it and I feared he had no parachute at all.

But almost as soon as I had that horrifying thought, I saw that the five other men, the professional skydivers, were working hard to get to the bearded man, and they were not panicked at all. They were like firefighters or lifeguards, putting their training into action, confident of their abilities to do their jobs and save a life. As I watched, they surrounded the bearded man, grabbing on to his hands and legs, holding them out like a puppet or a star. And working together, they pulled the hoodie from his body and I saw beneath it the straps of a parachute.

Their job done, the five others pulled the strings to open their chutes and fell up and backwards as they slowed above us. The bearded man, still panicked, continued his plummet. But I willed him to find his wits and the cord that would save him and he did. In the last possible moment, his parachute opened and he glided to the ground.

When he landed – in the city streets of Chicago, of all places, the other skydivers coming down atop buildings and billboards and somehow rappelling themselves safely to the ground – my bearded friend was met by another suited skydiver, this one a woman, helmet-less, who sat beside him on the curb, put her arm around his back and cradled his head on her shoulder as he sobbed his relief. “You’re ok,” she assured him, over and over. “You’re ok; it’s ok. You’ve made it; it’s ok. You’re safe.”

And as I sat in the passenger seat of our Mazda, listening to the tunes and the traffic, with my most beloveds around me in the car, I remembered my dreams. And the feelings of all these worlds – both real and subconscious – began welling within me. The fears of these times we live in, the genocide of my people, the devolvement of our society beneath our very feet. The anger and frustration that rise up in response to my own powerlessness. The joy and the contentment of this blessed life I live. The family and the work that fulfill my very being. The grief – oh the grief – at all that has already been lost and the preciousness of those who remain.

I held it all within me and it was so large a thing I carried that I could hardly breathe.

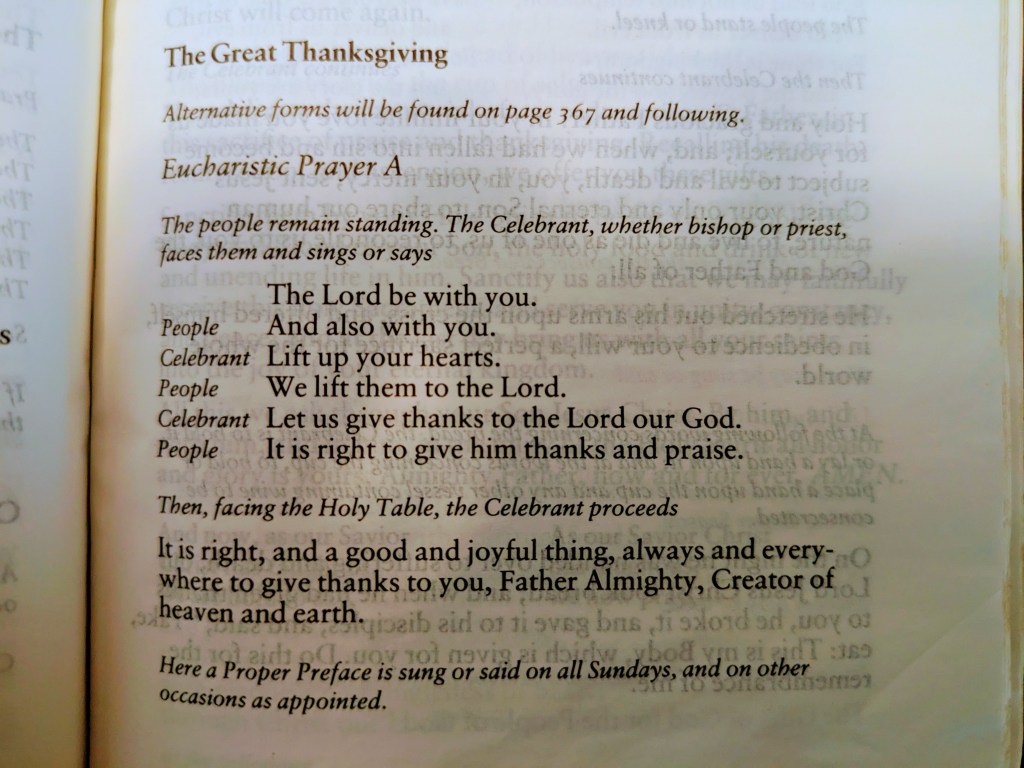

“Lift up your hearts,” sang the priest at church.

“We lift them up to the Lord,” we sang back to him.

The sursum corda has long been my favorite part of the Eucharistic liturgy. The reminder to lift up my heart always has me pushing back my shoulders, lifting up my chest, releasing all the stress of the week behind us and opening myself, my soul and body, to what the Lord provides.

But there was something new today that I heard in our ancient song. “Lift up your hearts,” we are told. Lift up your hearts, and all that is in them. Lift up your anger and your fear, your contentment and your satisfaction, your sorrow and your joy. Lift them up to the Lord and lay them on the altar at His feet. They are not yours to carry; they do not burden your soul.

And when I did so, I found that all that was left for me was the grief – the good kind, the kind that cozies up and reminds you of all the ones you have ever loved – and the gratitude, the thankfulness as pure and holy as a child’s as she holds her father’s hand, the relief of one who has long been falling to discover the firm foundation beneath his feet.

You’re ok; it’s ok. You’re safe now. I’m here.

“The soul that to Jesus has fled for repose,

I will not, I will not desert to its foes;

that soul, though all hell shall endeavor to shake,

I’ll never, no, never, no, never forsake.”

Leave a comment